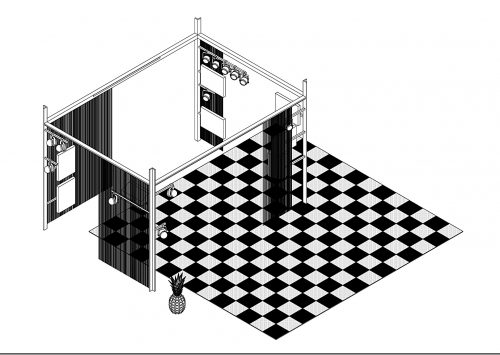

Research, spatial installation, video, 2016 10 images  The installation forms a (dance) space within the (museum) space, including video screens telling about the history of the “köçek.” The “queer boy” was a dancer, at the same time a slave and coveted star, of a courtly culture of pre-modern Islamic societies, in which more gender forms existed than allowed by the European masculine-feminine binary. The köçek performed mostly for male audiences and used various elements of self-design, including long, tiered skirts, tinsel, colorful silks, jewelry, and makeup. Colonial travelers identified the köçek as an effeminate, morally offensive (but desirable) figure of the deviant Orient. With modernization in the Tanzimat Reform (1839-1876), Ottoman civil and religious authorities adopted the Western heteronormative position and enforced strict censorship against the köçek, continuing today in homophobic policies.

The installation forms a (dance) space within the (museum) space, including video screens telling about the history of the “köçek.” The “queer boy” was a dancer, at the same time a slave and coveted star, of a courtly culture of pre-modern Islamic societies, in which more gender forms existed than allowed by the European masculine-feminine binary. The köçek performed mostly for male audiences and used various elements of self-design, including long, tiered skirts, tinsel, colorful silks, jewelry, and makeup. Colonial travelers identified the köçek as an effeminate, morally offensive (but desirable) figure of the deviant Orient. With modernization in the Tanzimat Reform (1839-1876), Ottoman civil and religious authorities adopted the Western heteronormative position and enforced strict censorship against the köçek, continuing today in homophobic policies.

The installation was accompanied by weekly DJ sets and invited all visitors and staff into a queer environment – to dance, that is, to mobilize our politically passive bodies.

There exist various words for “dance” in Turkish.

oynamak — to play, act, dance

raks etmek — (from Arab raḳṣ) to dance

dans etmek — (from French danser) to dance

göbek atmak — lit. to throw stomach, to belly dance

kivirtmak — lit. to fold, dance sensuously

These words come as metonymy, ready-made, reimport, or as hybrid, mixing Arabic, Persian, or French with Ottoman languages. If they constituted an index, it would refer to a volume of ambiguous performative practices, of temporary spaces and designs in precolonial Islamic cultures, recorded through festival literature as well as through travelogues.

If these words for dance constituted a provocation, it would ask for what is it between the subject who dances and the subject who rules?

To address this question, the figure of the köçek, a professional young male dancer, performing to mostly male audiences at the Ottoman court from the 16th to the 19th century, might establish a historical link. Often times recruited or even kidnapped from the non-Islamic population of Greeks, Jews, Roma, or Armenians the young dancer would start a six-year long education, including playing accompanying instruments. As long as he was “moon-faced,” the köçek was to perform and use diverse elements of costume and self-design, including long, tiered skirts or loose pants (şalvar), shimmies, colorful silks, jewelry, make up, and long hair, to enhance his beauty. We say his beauty, but we know that in both, old and modern Turkish there exists no gender-specific pronoun.

This “queer boy” was a part of precolonial Islamic cultures that tolerated ambiguous (even contradicting) social and cultural forms; above all, more gender forms and also with different temporalities than the masculine-feminine binary of European human design. Perceived as “normal” in Ottoman culture, the köçek appeared shockingly deviant to European observers. To both he obviously was desirable:

Traveling to Constantinople in 1810, John Cam Hobhouse reports: „… here I saw a boy dancing in a style indescribably beastly, scarcely moving from one place, but making a thousand lascivious motions with his thighs loins and belly.“ Two days later he brought Lord Byron to see the performance.

In the first part of his improvised performances, the köçek would move to slow music using a veil or a shawl. The second part would be livelier, and the dancer would employ wooden clappers, shimmies of his shoulders and hips, and involve sexually explicit movements. He would mime stories to elaborate his songs, and sometimes he would include skilled athleticism, acrobatics, and mimicry.

If the köçek was appreciated as an artist, he was above all an object of desire and sexual attraction, and a subject of sexual services. His performances caused rampage among audiences and even murders—murders out of jealousy, not because of issues with sexuality. Sexuality, as a concept designed to discriminate all sexual activities between homo or hetero was simply not existing in pre-colonial Islamic societies. It was only introduced through European colonial modernization.

Importing their set of gender and sexual scripts to the Islamic world, European observers would describe the köçek as effeminate or cross–dressed, even though he had his own unique style, neither male nor female. Ultimately, the köçek was re-designed according to European norms of gender and sexuality: He became a “homosexual”, morally offensive figure of the deviant Orient. During modernization, in the Tanzimat reform era (1839-1876), both Ottoman civil and religious authorities adopted the Western position, renounced the köçek for lascivious behavior and enforced censorship policies.

Alt Art Space, Istanbul Design Biennial, 2016